When Mali created a truth commission to address decades of conflict, it soon required specialized expertise. Working together with a JRR expert, the truth commission now has the tools it needs to bring together victims and gather truth, with method that is uniquely their own.

Text and photographs by Hannah Dunphy

On the night before he was to travel to Kidal, Colonel Major Haidara Aboucarine awoke suddenly from a bad dream.

It was May 2014, and Aboucarine was working as an officer for the government of Mali. At the time, the north of the country was contested by Touaregs belonging to the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) and other groups fighting for independence in northern Mali. In the town of Kidal, a stronghold of these groups, the situation was tense in anticipation of a visit from Mali’s Prime Minister. Aboucarine had been summoned personally by the Governor of Kidal to lend his assistance.

Aboucarine’s nightmare had been vivid, and given the ongoing violence in the north, others may have interpreted it as a bad omen. But Aboucarine—a devout Muslim and deeply spiritual man—was not one to be easily shaken. After praying for a short while, he returned to bed.

“I am an optimist,” he later recalled. “I never thought they would take Kidal.”

Days later, Aboucarine was on hand when Prime Minister Moussa Mara arrived in Kidal. It was then that several armed groups began an attempt to seize the town: men on trucks stormed the governor’s office, killing workers in their path. In the midst of the chaos, Aboucarine fled with a group of others into a house. He crouched his tall, lanky frame behind a wooden table, holding his breath as the house was searched. He listened as others who had hid were either taken away or shot. Hours later, Aboucarine too was discovered.

“The first man gave me water, but the second beat me,” he said. “They beat me on the head until I fell to the ground.”

Outside the house, his captors covered his head and shoved him into a truck with several others. The group was taken to a second location where they were packed into a small, hot room. With their hands bound, they were forced to lie on their stomach. In addition to the wounds aching on his head, Aboucarine broke his clavicle as a result of the rough treatment. They were held for nearly two days.

“They treated us really harshly,” said Aboucarine. “It was so hot in the room, it felt like there weren’t any windows. Some of us were ready to die. And some among us did.”

It was later revealed that the armed groups seized the Governor’s office, causing the Malian military forces to retreat, leaving the town under control of the militants. Haidara survived, but many did not: eight civilians, including six civil servants, were summarily executed by the armed groups.

The May 2014 events in Kidal made headlines around the world, yet it was only one incident in a long history of conflict in Mali that has commanded international attention, including a major coup in 2012, and before that, decades of uprisings, tensions and violence involving several communities, and gross human rights violations. Today, nearly four years later, only a tenuous peace agreement prevents Mali from splitting wide open again. Several Islamic extremist groups have regained strength, and drug trafficking and transnational crime through the Sahel makes security unpredictable. Restaurants and hotels frequented by foreigners have been attacked repeatedly, as have military checkpoints and UN vehicles.

Midst ever-increasing militarization, Malian human rights organizations remain concerned with the lack of security for civilians, where daily life continues to be disrupted by closure of schools and limited access to fields and jobs. A major UN peacekeeping force has been put in place, but near constant instability has made its mission in Mali the most deadly of all UN peacekeeping missions in the world. Citing the deteriorating humanitarian and human rights situation, the UN recently described the situation in Mali as “a race against time.”

It is in this tense atmosphere that a group of Malians have set out to achieve the unthinkable: bring splintered communities of Mali together for a national effort of truth and reconciliation. The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission of Mali is tasked with establishing the truth about Mali’s ongoing relapses into conflict since it gained its independence in 1960. An outcome of a peace agreement, the Commission is led by commissioners who represent each of the numerous different political, ethnic, and religious groups in the country.

For victims like Aboucarine who have grown tired of impunity for crimes such as those in Kidal, the Commission represents a new hope. But with ongoing violence in the country and significant challenges blocking the road to peace, the question remains: will the truth commission be able to heal the wounds of Mali?

- Streets of Bamako, Mali

PART I

Mali is large, land-locked country in West Africa and central Sahel. Huge swaths of desert comprise most of its northern territories, which reach deep into the Sahara Desert and share long borders with Mauritania, Algeria and Niger. Majority Muslim, Mali has produced dozens of Afro-pop stars like Salif Keita, and is famous for signature sounds of kora masters like Toumani Diabaté and Ali Farka Touré. Bamako, the capital city, is built along the southern banks of the Niger River, and has experienced a population surge in the past decade, including due to displacement by conflict in the region.

The majority of Malians have seen multiple chapters of conflict throughout their lifetime, dating back to 1960, when the country gained its independence from France. A military-led regime ruled Mali from 1968 until a coup in 1990, leading to elections of three successive presidents. There have been deep-rooted tensions between communities in Mali, which have only intensified the many political and cultural differences in the population.

The Touareg peoples reside mainly in the north of the country. Their grievances against the Government of Mali go back decades, as does their desire for independence. The most recent series of rebellions in the north began in 2011, when Touaregs who had been living in Libya returned to Mali; at the time, Islamic radical factions aligned with al-Qaeda were vying for control over territory and trade routes through the Sahel.

In January 2012, armed groups launched an offensive against the Government, and the military coup that followed threw the country into crisis. Islamic militants seized cities in the north, controlling them for almost a year under strict Islamic law. Only after a military intervention by the French did the Malian Government regain control of the north. In 2013, the UN Security Council established the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) to help the Malian military maintain control of the central and northern territories. Yet these regions of Mali continued to be the battleground for various factions of Islamic extremists and other armed groups seeking to demonstrate their strength, including the siege of Kidal in 2014.

New rounds of negotiations for a peace agreement successfully brought together the Government and organizations of armed groups (known as the Coordination of Azawad Movements and the Platform of Armed Groups). Provisions in the proposed agreement included a set of measures for justice and reconciliation. These were significant, because at the time of the negotiations, Mali had seen little progress to investigate and prosecute perpetrators of serious crimes, despite demands from victims’ organizations. The International Criminal Court (ICC) had also been active in Mali following the 2012 crisis, but its role has been limited (the ICC convicted Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi for his role in attacks against religious buildings and historic monuments). Through consultations in the peace negotiations, it was decided that Mali needed a process—a Malian-owned process—through which to address its legacy of violence.

The Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali was signed in May and June 2015. On justice and reconciliation, the agreement aimed to “prevent impunity and promote genuine national reconciliation” and included the implementation of the truth commission. With a mission to promote “lasting peace through the research of the truth, reconciliation and the consolidation of national unity and democratic values”, the current Commission Vérité, Justice et Réconciliation du Mali (CVJR) was born.

—-

Since the 1980’s, some 50 truth commissions have been created around the world with the intention of confronting widespread violence or societal trauma. The most recognizable of these is the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and today, truth commissions have been set up in countries as diverse as Canada, Peru, Tunisia, Cote d’Ivoire, and Nepal, with mixed results. Truth commissions are considered a cornerstone of transitional justice; part of a set of measures meant to address massive human rights violations of the past. For many post-conflict or post-authoritarian countries, the use of truth commissions sometimes has to do with the limited nature of criminal trials: after conflict violence, prosecuting every last person for their crimes can not only be daunting logistically, but can be perceived to risk efforts of social reconstruction—especially when a significant portion of the population has participated in hostilities. When conducted with a victim-centered approached, a truth commission can offer voice to survivors and acknowledgement from authorities about abuses of the past.

The truth commission in Mali is ambitious. The mandate of the CVJR is to investigate and establish the truth about human rights violations or infringement on memory and cultural heritage spanning back to 1960. It is also expected to: propose remedies for crimes committed; create conditions to facilitate the return and reintegration of refugees and displaced persons; promote dialogue and peaceful coexistence between communities and with the Government; promote rule of law, and propose approaches to conflict prevention. The CVJR has no less than 25 commissioners, women and men representing the ten regions of the country and the full diversity of Malian ethnicities, religious groups, and political parties. Commissioners lead the work of five subcommittees: truth-seeking; victim support and reparation; studies, reports and documentation; awareness-raising and reconciliation; and gender. In addition to its headquarters in Bamako, the CVJR has expanded its presence by way of regional offices throughout the country, including in Mopti, Segou, Timbuktu, Gao and—when security allows it—an office will be opened in Kidal.

As it set out to organize its approach, the CVJR had access to decades of existing human rights documentation conducted by the UN and others. With the help of additional mapping exercises, the CVJR soon had a litany of crimes to consider: summary executions and extrajudicial killings; enforced disappearances; torture and ill-treatment; violations of freedom of expression; sexual violence, and grave violations against children.

To hear personal accounts of these incidents, one of the first things the CVJR set out to do was to begin gathering statements from victims. With help from its regional teams, a call was sent out to all Malians, inviting them to provide an official statement to the Commission. The response to their call was huge: by July 2017, 4,466 depositions (including 2,837 from women and 19 from children) had been collected by the CVJR.

When the Commission’s staff began to input the statements into its database, however, inconsistencies appeared, and it soon became clear that not all of the information that had been collected was accurate. It’s speculated that this may have been due to victims’ expectations that their participation would secure financial compensation from the Government.

The CVJR knew that the perception of falsified information threatened to undermine the legitimacy of its work. But with limited time or resources, going backwards was not an option. How was the CVJR going to successfully gather victims’ stories?

With limited expertise in-country, the CVJR turned to its international supporters for advice, and Switzerland soon reached out to the operations arm of Justice Rapid Response (JRR) in Geneva. The organization manages a standing roster of experts, more than 650 individuals from around the world, who specialize in areas such as international investigations, prosecutions, and technical workings of transitional justice measures like truth commissions. After close consultations with the leadership of the CVJR, a transitional justice expert from the JRR roster was identified by the CVJR and invited to Mali. Weeks later, in May 2017, Hernando Caceres of Bogotá, Colombia arrived in Bamako and got to work.

A pedestrian walks along the road to Koulouba.

PART II

The headquarters of the CVJR is in an area called Koulouba, which sits atop a lush hill overlooking Bamako. To reach it from Bamako city center requires travel through a maze of streets—some of which are paved, most of which are not. In Bamako, daily life unfolds outdoors. The city sits on earth that is a bold and burnt red, producing a dry dust that covers clothes and animals, and billows out behind the constant stream of motorcycles. From very early morning the air is already warm, the roads already thronged, and the markets abuzz with color and activity. Women in brightly patterned skirts sell eggplants, limes, and tomatoes displayed on plastic tarps. Men gather at makeshift barber stations, and goats cluster next to towering piles of green watermelons. Children walk together with colored backpacks, or play games of soccer under billboards advertising packaged, brand-name products. In the final ascent towards Koulouba, the paved winding roads and overgrown trees are a welcome respite from the city. Snaking switchbacks lead to a large complex of government buildings, guarded by a military checkpoint.

Frequently in the past six months, Hernando Caceres has made this daily journey to reach his temporary office at the CVJR. Hernando, 41, is tan and slender, with a neatly trimmed beard. Alert and extroverted, he is quick to flash a wide grin when seeing someone he knows (which, even in his temporary home of Bamako, happens often).

When he first arrived in Mali, Hernando examined the problem of the inconsistencies in the victim statements. Early on, through consultations with the Commissioners and their staff, it became clear that it would be impossible for the CVJR to investigate the validity of each deposition. Even if the CVJR had the time and resources (analysis of each deposition took staff nearly three hours per document), Hernando knew that the process of investigating each story could be potentially harmful—even re-traumatizing—to victims.

The sensitivities around victimhood is something Hernando knows a lot about, and not only through his role as a technical expert. Growing up in Bogotá, Colombia, Hernando and his family were victims of the Colombian conflict. His uncle had been kidnapped by the FARC rebel group and was never heard from again.

“I saw how families, friends were affected when the country was going from bad to worse,” says Hernando. “I knew I needed to be part of the answer.”

Hernando Caceres at the headquarters of the CVJR in Bamako

After finishing university in Colombia, Hernando continued his education in France, and then went on to work on post-conflict dynamics in Cambodia. He worked on human rights issues in Burundi, and later returned to Colombia, where he joined the National Commission of Reparation and Reconciliation (Comisión Nacional de Reparación y Reconciliación, or CNRR), a body he says is responsible for planting some of the first seeds of truth and reconciliation in Colombia. Hernando also worked with the UN Development Programme on projects to foster coexistence, reconciliation, and community-based reintegration of former combatants in over a dozen regions of Colombia. Later, he joined the UN Peacekeeping mission in DR Congo where he also worked on transitional justice issues.

It was with the CNRR in Colombia, however, that Hernando saw the real value of knowing the truth about a painful past: through the work the truth commission, Hernando and his family finally learned for certain that his uncle had been killed in the conflict. It showed Hernando firsthand how simply knowing the truth about what happened can change everything.

“When a person is kidnapped or forcedly disappeared, life doesn’t continue for his or her relatives,” he explains. “Normally when somebody dies, you go to the cemetery and you know they are there, and life continues somehow. But when you don’t know what happened to your loved one, you expect them to come home any day, every day. That’s when I understood that truth is the best way to repair victims. Because the truth repaired us.”

As a skilled expert in transitional justice, Hernando was recruited by JRR and certified to its expert roster, becoming eligible for international deployment to bodies that come to JRR looking for specialized expertise. Later, when JRR called with an offer to deploy to Mali, he accepted at once, ready to share more comparative knowledge with a conflict-affected country.

This is just one of the many ways Hernando feels a great sense of solidarity with Malians as they address their past, and here at the CVJR, he finds himself in good company: several of the commissioners and CVJR employees are victims of conflict themselves. Some are former combatants. But the mission of the CVJR has brought them under the same roof. Knowing Hernando is also from a conflict-affected country has made a difference in his day-to-day interactions with the Commission, and they have found they share more than they thought. For example, both multi-generational conflicts in Colombia and Mali are exacerbated by illegal drug trades. What’s more, Hernando explains, is that many drugs smuggled out of Colombia and shipped across the Atlantic are moved directly through the Sahel—including through Mali—in order to reach European and Asian markets.

“Being from a country that has suffered an internal conflict gave me a lot of credibility here in Mali,” says Hernando. “We speak the same language: the language of suffering. But also, of reconstruction.”

Hernando, in his office, looks through drawings created by victims of conflict

A victim-centered approach, rather than investigative, was what Hernando eventually proposed to the CVJR: instead of asking for Malians to make individual statements, the CVJR would facilitate collective consultations, where a group of victims of a specific incident would reconstruct the truth together. A collective, representative methodology—which has been implemented in other transitional contexts—would allow victims to recreate their truth; not ask them to construct ‘the truth’ or ‘a truth’, but multiple truths at the same time. Counter to what some may assume, Hernando says a truth commission is not about agreeing but rather presenting a multitude of perspectives back to society.

“Collective memory helps overcome the challenges that individual memory has,” says Hernando. “It helps re-create events in a more precise way than individual memory. For example: if I ask you, ‘What did you wear last Monday?’ Do you remember? Of course not. But if I gathered your friends and co-workers and asked them, together we could probably figure it out.”

The CVJR agreed with the new approach. Hernando, acting as educator and mentor, first worked with staff members—some of them victims of conflict—to show how collective methodologies are facilitated. One of these is called “Collective Scars”. First, victims are asked to draw the outline of their body, or have it traced by laying down on a large piece of paper. Then, using the drawing, the facilitator starts asking questions about scars—both visible, and invisible.

“We first ask participants to tell us what happened to them early on in their life, before the conflict,” says Hernando. “We start with physical scars from the past–maybe I broke my arm when I was young, or scraped my knee, so I would draw that. Then, using specific methodologies that do not re-victimize participants, I ask them to draw invisible scars: I ask, ‘Was it hard growing up? Were you bullied at school?’ And then from there, we eventually go into events of the conflict. As a facilitator, I know that I want to arrive at the hardest thing to talk about—rape, for example. But in order for them to speak about rape, they first need to feel comfortable talking to the group about their scars.”

In total, Hernando offered five different collective methodologies to reconstruct truths and memories of victims and former combatants. As the CVJR staff learned the methodologies, they ran into some cultural challenges. For example, in Mali, when elders speak in a group, younger people do not contradict them. Gender dynamics were a challenge, too, where issues like sexual violence were too sensitive to discuss in a room with both men and women. Together, the group suggested solutions, and adjusted course.

“I was clear that I would teach what I knew, but then Malians would adapt it to make it work for them,” says Hernando firmly. “They have already started to ‘Malian-ize’ the methodology. It’s theirs now.”

Commissioner Mohamed El Moctar Ag Mohamedoun at the gate of the CVJR headquarters

PART III

It’s Monday morning and the CVJR commissioners and staff meet for their weekly plenary meeting. Outside, the sun is already hot, and the shades are drawn over all the windows of the conference room. Hernando is the first to arrive; it’s his last meeting with the full leadership of the CVJR.

Men and women begin to filter in. Most are dressed in stately sky blue or white cotton garb that reaches down to their knees or ankles. Hernando greets everyone with a smile and a handshake. It is soon a buzz of greetings in French, Bambara, Tamasheq and Arabic. Daily salutations go on extensively here, where a simple “Hello” doesn’t suffice. The room fills with earnest questions: “How are you feeling today?” “How is your health?” “And your family? How are they?”

One elderly commissioner enters the room with a smile; upon seeing Hernando, he raises both arms joyfully and bellows out “Buenos días, Hernando!” and laughter fills the room. Hernando blushes and grins from ear to ear.

The 25 commissioners sit at a long wooden conference table, and Hernando sits along the wall with observers representing UN agencies and European donors of the Commission. As the meeting begins, the room transforms into a pantheon for the guardians of this process. In the collegial atmosphere, one might momentarily forget that some of the interests and agenda of these groups have been at odds for decades: nine of the commissioners represent armed groups.

One commissioner at the table sits in stillness for most the meeting, watching and listening intently. When he does raise his hand to speak, the room falls into silence. Commissioner Mohamed El Moctar Ag Mohamedoun, a Touareg from the north of Mali, is the representative of the Coordination of Azawad Movements to the CVJR. He wears a traditional chech which wraps around his head and covers much of his face. Despite a serious demeanor, he is visibly one of the youngest amongst the commissioners.

Like many around the table, Mohamed’s reasons for participating in the CVJR are deeply personal. Growing up in the Sahara, Mohamed and his family lived in refugee camps. Later, speaking from his office, he says his family had almost nothing. Mohamed’s voices is deep, steady and resolute; his eyes, dark and direct. As he speaks, his poise is not unlike that of a diplomat, keeping his hands folded carefully on his desk as he speaks.

“I know Mali from the north to the south,” he says confidently. “My family and I were victims our whole lives. I know what the victims in Mali are feeling because I was a victim too.”

Commissioner Mohamed El Moctar Ag Mohamedoun at CVJR headquarters

The Touareg people have struggled for decades to gain political and territorial autonomy in Mali. Seeking jobs and better livelihoods, in 1963 and then during the 1970s and 1990s, thousands moved to Saudi Arabia, Mauritania, Algeria as well as Libya, where Muammar Gaddafi welcomed them and integrated many into the Libyan army. After Gaddafi’s death, many in Libya left and returned to Mali, carrying with them weapons, military training, and new determination.

After earning a scholarship and studying in Morocco, Mohamed returned to live and work in refugee camps in Mauritania, where he attended primary school, just in time to see the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA – French acronym) emerge. He joined the MNLA, and soon became a spokesperson for the Azawad cause. Later, when the CVJR came into being, Mohamed knew he wanted to be a part of it, even though relocating to Bamako would bring him far away from his friends, family, and community.

“In Mali, justice has never has been done, and neither has truth,” he explains. “That’s why conflicts are coming back. But we cannot do justice to things we don’t know.”

With the staff members of the CVJR’s sub-commission on truth-seeking, Mohamed has worked with Hernando on a daily basis. He is now among the staff members who has been entrusted with the new model of collective consultations, which he sees as a way for the CVJR to collect more stories and perspectives in a shorter amount of time, and the process is a collaboration between victims and the Commission.

“Hernando has helped us a lot. He has showed us the essential strategy of investigations, investigator profiles, and different techniques of collective consultation with victims,” he says. “Through Hernando we have begun to put this strategy in place.”

Colonel Major Haidara Aboucarine, Bamako.

PART IV

With the methodologies adapted for the Mali context, it came time for the CVJR to bring it to the community. After careful deliberation over many potential cases, the CVJR announced that the first group of victims to be convened would be survivors of the May 2014 attack on Kidal. Victims were identified and 12 men came to the Bamako Regional office for the first official collective consultations.

When Colonel Major Haidara Aboucarine received the invitation to join the consultation with the Commission, he accepted without hesitation. The years since surviving Kidal had challenged him a lot. His physical wounds had healed, but he says he struggled psychologically.

“After the CVJR called me, I went and told my story,” said Aboucarine. “We spoke for those who were not there. We spoke for people who were killed.”

Working together for three days, the group talked through the events of the Kidal attack. Just as Hernando expected, many new details came to light. The group that had been captured with Aboucarine reconstructed what had happened. One man, remembering being bound and blindfolded in the stifling heat, said he was certain that the room had no windows. Many agreed. But one man did not: he had overheard the guards speaking with one another in the Tamasheq language—which the man understood—and recalled that the guard had been instructed to open one of the windows in the room, to give the prisoners some air.

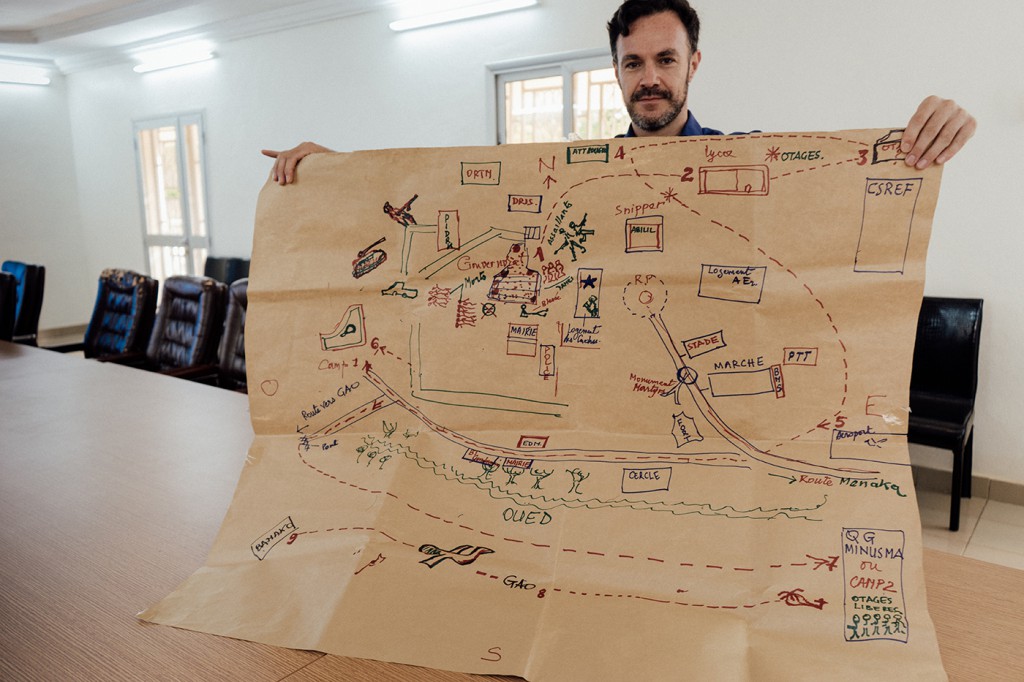

Through conversations like this, victims helped each other bring the past into focus, no matter how small the details. The group slowly reconstructed every event of that day, even creating a large map of Kidal, with indications of where different incidents occurred.

Recounting the emotions of the reunion, Aboucarine says there were many tears. But there was also laughter.

“It freed people,” he said. “The people have put their trust in the CVJR, and the CVJR will set us free.”

The detail-rich information of the Kidal attacks will be entered into the CVJR database, eventually to be published in a CVJR report alongside other accounts of major events since 1960. Soon after the initial consultation was successfully held, CVJR President announced that the Commission would adopt the collective methodologies for all of its future consultations with victims. The next task would be to bring the methodology to all the regions of Mali, including in Ségou, Mopti, Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal.

Hernando displays a map of the events of the Kidal 2014 attacks, as created by victims through collective consultations

As the ones who had adapted the methodologies and completed the first collective consultation, it is the task of the staff of the Bamako regional office to help carry the knowledge forward. The Bamako office is in another part of the city, away from CVJR headquarters in Koulouba, so that it can be easily accessed by those who want to tell their story. The office is a sparse concrete building that feels more like a house than an office, room enough for the nine people who work there.

Heading the team is Ms. Diop Djènèba Mariko a young Bambara woman who began working at the CVJR in August 2016. At the modest office premises, her petite frame is dressed in a long striped skirt and matching jacket, and her hair is neatly pinned back. She has a quiet, unassuming presence amongst the staff she manages, but when she speaks, it’s with a relaxed confidence, and everyone listens.

A long-time human rights advocate in Mali, she sees the CVJR as a natural place for her to be. Over the years, she has also been a champion for the rights of women and children, and points to the differential impacts that the conflicts in Mali have had on women, such as widespread displacement, limited economic opportunity and sexual violence. Through the truth that the CVJR can reveal, she hopes Mali can offer remedies that respond to the situation of women who have lost everything.

“I saw how Bambara women were suffering, without any opportunity to speak,” she says. “This is why I began to work on these issues, for women’s freedom to express themselves.”

Ms. Diop Djènèba Mariko, head of CVJR Regional Office in Bamako

Djènèba and her staff have steadily received victims who have come to tell their story. Some speak comfortably and can provide great detail. Others have a lot of psychological difficulty relaying what they can remember. She says the staff had worked a lot to make sure victims receive the support they need. Now, the staff is ready to take the methodology forward to an even wider group of victims.

“We are thankful to JRR for sending Hernando to us,” she says. “We have learned many things, and it has helped us so much. Better than individual consultations, we can get more information, and that information is often even more detailed than what we get from only individual consultations. Because of what we have learned, our office can now offer training to others on truth-seeking techniques.”

In October 2017 as his mission came to end, one of Hernando’s last stops was here to the Bamako office to say goodbye. With Djènèba, the group gathers in a sitting room with leather couches, where they review drawings that had been created as part of the consultations—each shaky outline representing the body a survivor, and no outline without indications of multiple scars. Hernando lets them do most of the talking, listening intently, and at times providing nods of encouragement.

Like many others here, Djènèba is also supportive of the process being one that is nationally-owned, rather than international. Having all Malians participate—including women—will be how the CVJR will be a success.

“We have a saying in Mali,” she says, smiling, and with careful emphasis. “Which means, ‘The prisoner is well-placed to speak of the prison where he is held’.”

Later, Hernando is convinced to be in a group photo in front of the large metal sign for the regional office. There are handshakes and laughter, and insistent requests that Hernando return soon to Bamako.

As the group says their goodbyes, directly across the road is a small lot of land, overgrown with weeds, and flanked by dilapidated concrete buildings. The lot is mostly empty save for one young tree that stands in the very center, its slender trunk growing straight and tall, its leaves a rich green against the washed-out buildings behind it. The tree almost seems like a mirage, new energy emerging from the red dust of Bamako, ready to grow.

A tree grows across from the CVJR Regional Office in Bamako

EPILOGUE

On his last day in Mali, Hernando sits on the garden patio at an enclosed café that is a favorite of internationals working in Bamako. Under the shade of trees and birdsong, it’s easy to forget the headlines of the day: international actors drum up support for counter-terror efforts in Mali as part of the new G5 Sahel Joint Force, more UN peacekeepers killed, and new security threats are reported against hotels in Bamako.

Sitting at a small table with a coffee in hand, Hernando is reflective. Later that night he would be returning to Colombia for a short time (“Long enough to do my laundry!” he says, laughing). He’d then return to an undisclosed location in Africa, another conflict-affected scenario where his expertise is needed. Hernando is more than confident that the work will carry on here in Bamako well after he leaves. When asked what his parting words would be to the staff of the CVJR, he answers without missing beat.

“Trust yourself. You already have everything you need.”

This perhaps has been Hernando’s most important contribution: creating capacity of Malians in Mali. It’s of no surprise to those who know him that he dislikes being referred to as an “expert”.

“Experts create dependency,” he says. “In some cases, experts do harm: they come, they write a report, and then they go, and nothing stays there. We suffered that a lot in Colombia—people came from different parts of the world, and then they left.”

Fortunately for Mali, the CVJR has the tools it needs to bring together victims and gather truth, with a “Malian-ized method” that is uniquely their own. The CVJR is just a start for country to face its past, but it is a chance to take charge of their own history, and, with time, perhaps their future, too. Hernando is already thinking about when it will be Malians who will be sharing their experience to other conflict-affected countries looking to learn from the “experts”. But for now, a group of unlikely allies in Mali are at work, steadily sifting through shadows of the past, as the red dust continues to settle.

—

Acknowledgments

JRR would like to thank the CVJR for receiving JRR in Mali for the production of this article and to all who were interviewed.

The work of Hernando Caceres with the CVJR and this article made possible with the generous support of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland.

Available in French here | Additional photo editing provided by Esteban Hernandez.

Learn More about JRR’s work to assist national jurisdictions seek accountability for serious crimes here.

Learn more about Switzerland’s commitment on Dealing with the Past here