The process of creating art can be an outlet for expressing unspeakable pain for victims of war crimes, or in the case of artist and former war crimes policy adviser Jaye Ho, releasing frustration when faced with impunity and the slow pace of international justice.

In her exhibition – “The Vanishing Act” at the ONCA gallery in Brighton, UK – Jaye explores through her work how injustices are collectively remembered, or erased. The intersection of art and conflict was analyzed at an online event near the conclusion of her show, with transitional justice specialist and Justice Rapid Response Roster member Hernando Caceres suggesting that the healing process that can come about from drawing is itself “art”.

Seen from this perspective, the power of art is to give a voice to the once voiceless, or to communicate what is not easily communicated, as well as to collectively identify truths that can heal. Justice Rapid Response sat down with Jaye and Hernando – remotely – to find out more.

Healing through art

Hernando, in his transitional justice, human rights and protection of civilians work, frequently uses drawing as part of a technique to allow survivors to begin speaking about their traumatic experiences. In 2017, Justice Rapid Response deployed Hernando to support Mali’s truth commission, known by its French acronym ‘CVJR’, in gathering victims’ stories.

“You give victims the opportunity to be heard,” said Hernando. “They have been silenced, they have been threatened, they couldn’t complain or speak up for decades. No one cared what they said.”

Established following Mali’s Peace and Reconciliation Agreement of 2015, the CVJR has a broad mandate to examine violence going as far back as the 1960s, and aims to tackle its root causes.

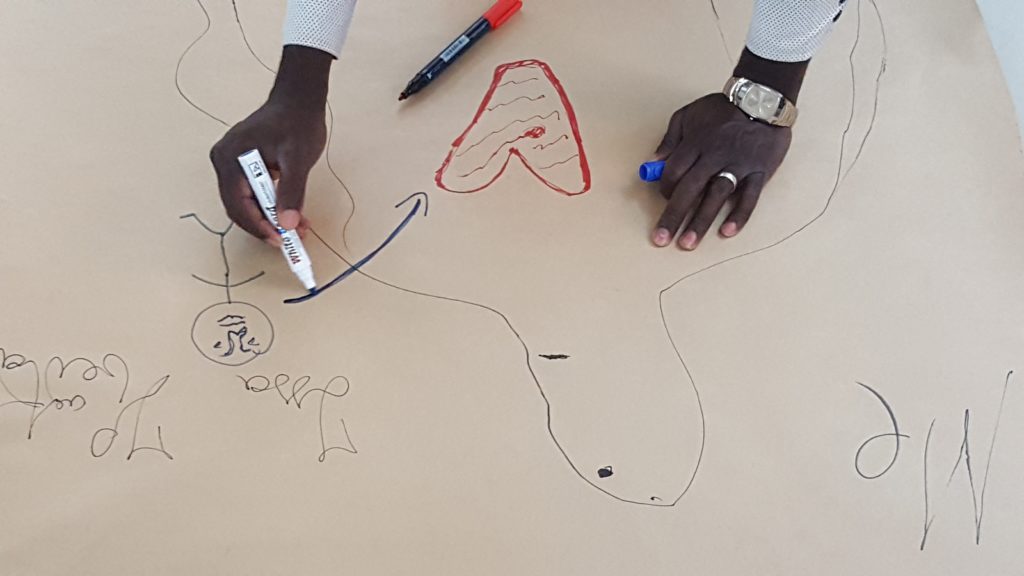

Creating a “paper mirror” in a truth and reconciliation workshop in Mali, copyright Hernando Caceres

Among the exercises in Hernando’s workshops, is the “paper mirror” in which he asks survivors to trace their silhouette and then identify areas of pain – starting with physical scars, before addressing the emotional ones.

By using a variety of such methodology – including drawing maps and timelines, and storytelling – in a series of sessions culminating in the collective drafting of a healing narrative of events and a townhall meeting, communities begin to heal.

“Through all these techniques, you are recreating the social tissue and trust,” said Hernando. “A survivor can say: ‘Now I understand why you did this to me, and I forgive you and I forgive myself’.”

When an individual starts their emotional healing, this helps to heal their family, and in turn this helps to heal society, says Hernando. The reverse is also true, and scars unhealed can mark generations to follow.

Art as testimony

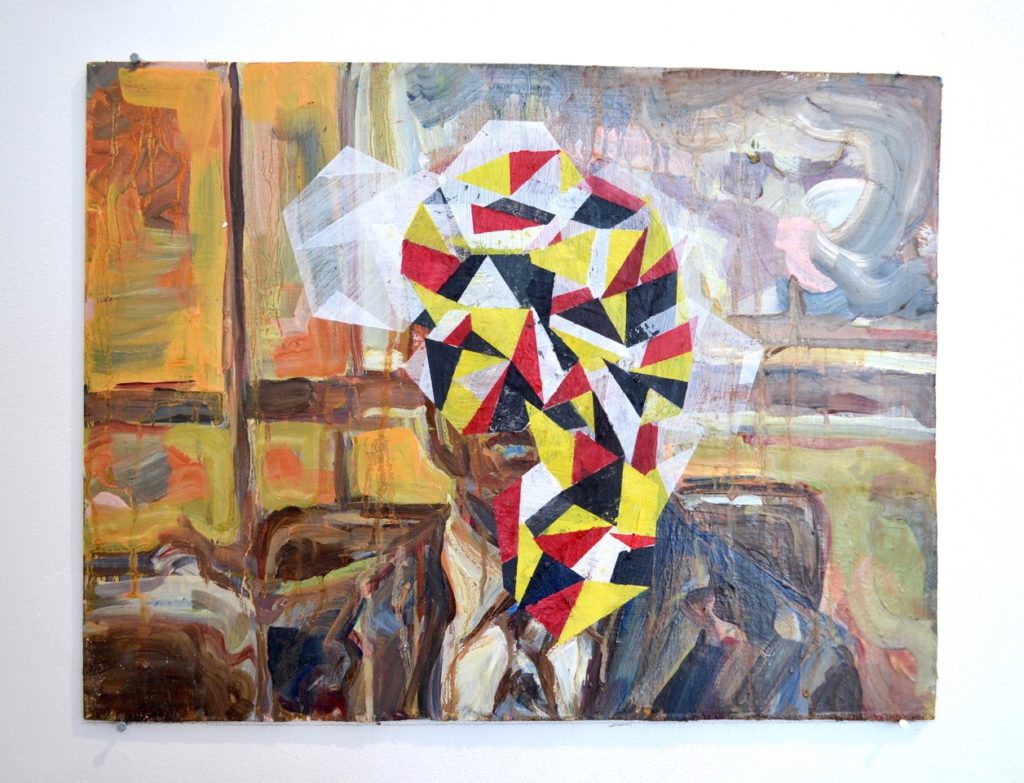

While Hernando uses art in his human rights work, Jaye’s human rights work – or job – is reflected in her art. An artist by training, Jaye also built a career in the field of international justice. In a previous role she held as the United Kingdom’s war crimes policy officer to the International Criminal Court, she began painting war criminals with their faces blotted out, as a way to express frustration over the difficult process of delivering accountability for victims and survivors.

This led Jaye to more personal reflections about why she is interested in human rights and war crimes, and she recalled what her mother told her about growing up in Japanese occupied Malaysia.

“At the time, my mum’s older sisters were 13 and 15 and had to cut their hair and pretend they were boys so that they wouldn’t be taken by soldiers and forced into sexual slavery,” said Jaye, whose exhibition also explores this use of ‘comfort women’ by the Japanese army in World War II.

As with her war criminal subjects, Jaye portrays images of victims – and those at risk of sexual violence – with their faces obscured.

“In the case of victims or survivors this symbolizes protecting them, whereas with perpetrators this is more of a condemnation,” she said. “There’s also a fine line between showing the atrocities of war crimes and glorifying them.”

Justice beyond the legal system

Jaye says that despite being recorded in history, the topic of comfort women is still a subject of debate and she has met people who deny that the practice ever existed. This is an additional reason driving her to portray survivors.

“The voices of female survivors often disappear from history and we are more likely to remember the suffering of soldiers as opposed to the suffering of civilians,” said Jaye, who is keenly interested in the female perspective of war.

In Hernando’s opinion, drawing needs to be used more widely in transitional justice. Not only is art not used enough in these processes, he says, but when it is, it is often misused to attract publicity.

“We need serious practitioners to train people to use these techniques properly,” said Hernando, who believes that every drawing contributes to a larger process of reconciliation.

“It’s justice, even if it’s not criminal justice. Putting pieces of the puzzle together, it becomes truth reconstruction.”

Jaye Ho and Hernando Caceres spoke to Justice Rapid Response in their personal capacities. The views cited here reflect their personal opinions and reflections, and not those of their respective employers.